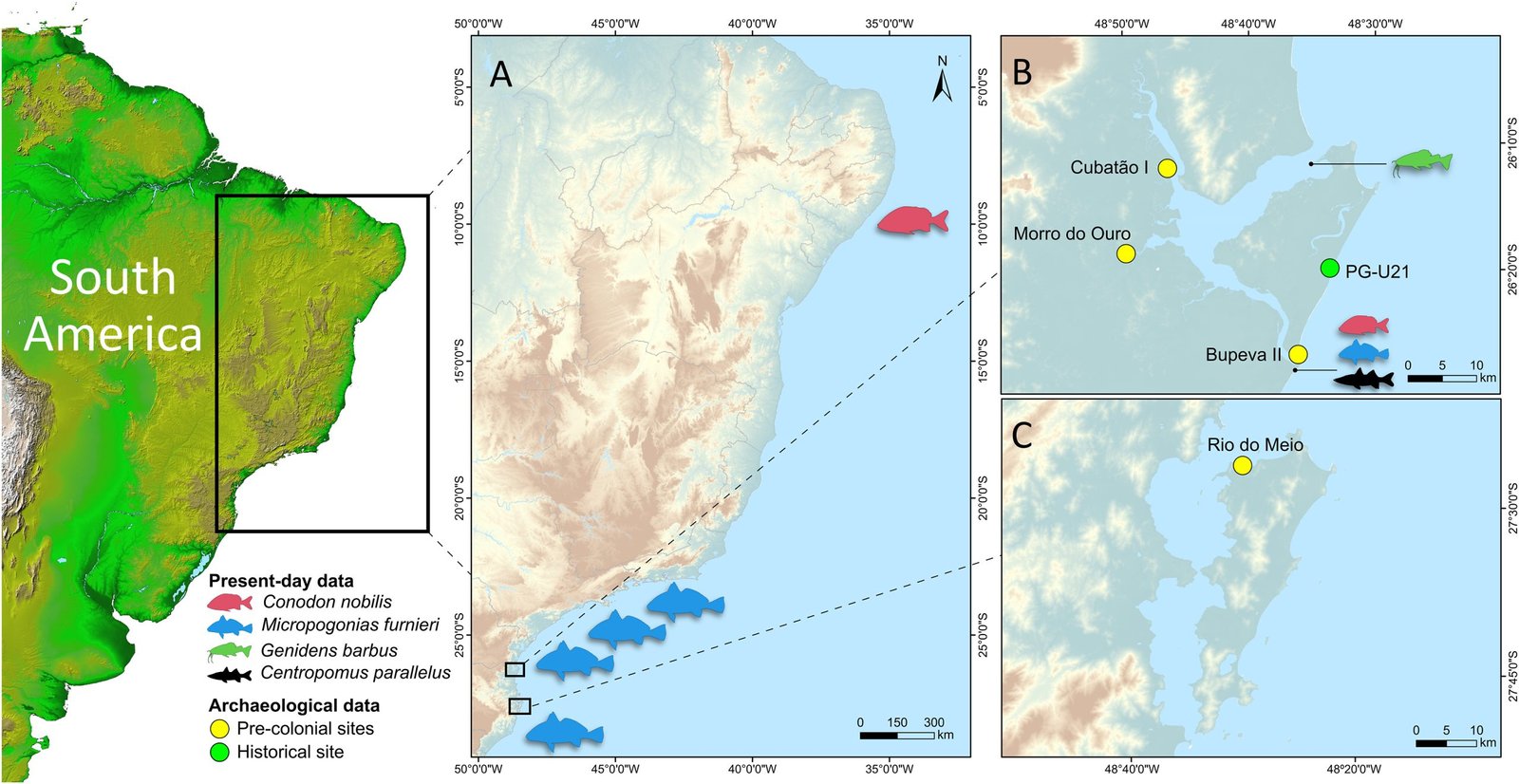

Human population growth and the technological advancements of the 20th and 21st centuries have significantly altered human-environment interactions and led to unprecedented anthropogenic footprints on coastal and ocean systems. Despite thousands of years of exploitation for subsistence and, later, commercial purposes, the ecology of mangrove fisheries along the Brazilian coast and the consequences of these activities remain poorly understood. This is largely due to a pervasive lack of historical baselines, and highlights the conservation crises affecting some of the world’s biodiversity hotspots. In this study, we used otolith metrics and stable isotope analysis to investigate changes in the body length and trophic ecology of several demersal species recovered from pre-colonial (4500 cal BP to 1500 AD) and historical (late 19th and early 20th centuries AD) archaeological sites in Babitonga Bay, the largest mangrove system in southern Brazil. Our results revealed that pre-colonial and historical fisheries exploited a wide range of mangrove habitats, encompassing brackish to marine systems. Pre-colonial subsistence fisheries, however, targeted predominantly small and juvenile individuals in nursery areas, while early commercial fisheries targeted larger adult specimens, likely due to their higher commercial value. Our study shows that some drivers of stock overexploitation, such as the preferential capture of large and adult individuals, were found to be occurring more than 150 years ago along the southern Brazilian coast. Given the deep roots of human footprints in Brazil, our findings underscore the significance of incorporating historical data into the formulation of fisheries management strategies in subtropical and tropical regions.